As seen in Psychology Today.

Despite rapid advances in all fields of conventional medicine, physicians still face limitations in available treatments. This most certainly includes psychiatrics. Consequently, in specific circumstances, physicians should acknowledge that patients may benefit from alternative forms of treatment. These alternatives include drugs and herbs that may be currently illicit according to the federal government, but have been a part of non-Western pharmacopeias for centuries, if not longer. One such drug is psilocybin, a powerful hallucinogen found within mushrooms of the genus Psilocybe.

A lot of attention has been given to psilocybin recently. This comes in the wake of numerous high-profile articles in the media on the subject, as well as the decision to decriminalize “magic mushrooms” (as they are frequently called) in the cities of Denver and Oakland, California. There have also been several studies that have examined the medicinal applications of this drug in a controlled environment. Thought his research is still in its infancy, researchers have found that psilocybin and other psychedelic drugs do have potential medicinal benefits that will be explored below. Despite its potential benefits, however, psilocybin and many other psychedelic drugs remain illegal in most jurisdictions and at the federal level. Psilocybin is a Schedule I drug as defined by the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 and all drugs classified as Schedule I are not recommended for recreational use.

It is not the purpose of this article to endorse self-medication. It is for educational purposes only. Should an individual decide to experiment with psilocybin or any other psychedelic drug, they should do so in a clinical setting or with a guide who has experience monitoring and caring for people while they are under the influence of such drugs. Psilocybin is a particularly potent psychedelic. It can produce unpredictable results; individuals who use psilocybin can have impaired judgment and/or act in a reckless manner.

Why They Are Called “Magic Mushrooms”

Psychedelic drugs have been used by numerous shamanistic cultures dating back to prehistory. For these cultures, psychedelics are not taken recreationally; they provide a means to communicate with ancestors and spirits that are believed to transcend the corporeal world with which we interact on a day-to-day basis. This is true throughout the world. It is also true that various types of mushrooms, chiefly those of the genera Psilocybe or Amanita, have often been the source of these psychedelics.

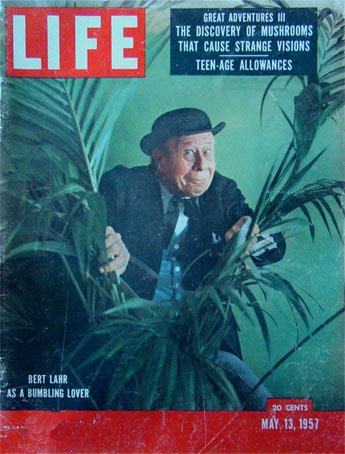

While the genus Psilocybe does have a worldwide distribution, it appears that its usage was most common among Amerindian tribes in Central America and Mexico. Usage became more common among mainstream Western culture largely due to R. Gordon Wasson, a mushroom enthusiast and banker from New York City. Wasson traveled to Oaxaca in 1955 and met a shaman who introduced him to both mysticism and mushrooms containing psilocybin. Wasson then published a story about his experience in a 1957 issue of Life magazine. The title of the article was “Seeking the Magic Mushroom.”

Wasson also sent samples to Albert Hofman, a chemist who had first synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide (more commonly known as LSD or acid) in 1938 by isolating compounds found in ergot, a fungus that affects rye kernels. Hofman isolated and synthesized psilocybin from the samples of mushrooms in 1958.

What Are the Effects of Psilocybin?

Mushrooms that contain psilocybin tend to induce profound changes in mood, thought, and perception by binding to and serving as agonist to serotonin receptors in the brain (specifically 5-hydroxytryptamine (HT)2A receptors). The experience (often called a “trip”) is highly variable and can be influenced by an individual’s mindset and environment (often known as “set and setting”). One will typically begin to feel the effects of psilocybin approximately 30 to 45 minutes after ingesting it, and the effects tend to last around four to six hours, depending on dosage. The “peak” of the effects, when they are at their strongest, typically occurs between two and three hours after consumption.

While auditory and visual hallucinations are common, those who take psilocybin may also experience deeply spiritual epiphanies that are difficult to fully recall once the drug’s effects wear off. Individuals who have participated in studies involving psilocybin have said that the experience can be lifechanging, and that it has allowed them to become more insightful and reflective. The drug can also produce a euphoria and a sense of connectivity with others or the world at large.

Data suggests that psilocybin is far less potent than a drug like LSD and that it carries a very low risk of overdose toxicity (estimated to be 1,000 times an effective dose), but it can still produce negative effects. Psilocybin has been known to produce side effects like hypertension, tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, anxiety, vertigo, confusion, and increased sensitivity to light due to dilation of the pupils. Furthermore, hallucinations can become very intense depending when dosages are large enough, and some individuals have been known to suffer from what is known as a “bad trip.” This involves unpleasant or even disturbing thoughts or hallucinations, which may lead to anxiety, confusion, delirium, and, in extreme circumstances, temporary psychosis.

Considering the data and clinical utility of psilocybin, people who would like to try it should only do so in a controlled and clinical environment or under the guidance of individuals who are experienced in the use of psychedelics.

Clinical Studies on Psilocybin

Though clinical studies on psilocybin have been difficult to perform in the United States since the passage of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, which put significant restrictions on scientific research on all substances classified as Schedule I drugs, limited research has been performed in the US and abroad. These studies indicate that psilocybin can effectively be used to combat anxiety and depression, particularly among individuals who are approaching the end of their lives due to terminal diseases like cancer. Mitchell et al noted that symptoms of this form of anxiety and/or depression occur in between 30% and 40% of cancer patients in hospital settings. However, therapies to address this problem are wanting. Writing in 2016, Ross et al noted that there “are currently no pharmacotherapies or evidence-based combined pharmacological-psychosocial interventions to treat this type of distress and unmet clinical need in cancer patients.

A study conducted by Griffiths et al that was published in 2016 found that a group with clinical anxiety and depression caused by their life-threatening cancer diagnoses largely reported improvements in mood and attitude directly after the consumption of psilocybin. During the follow-up six months later, these results were largely unchanged. A study by Grob et al produced similar results.

Ross et al, meanwhile, found that a single dosing of psilocybin, in conjunction with psychotherapy, effectively treated existential malaise brought on by the recognition of one’s impending death due to illness. The effects were sustained for as long 26 weeks, with the majority of patients experiencing anxiolytic and anti-depressant effects, improvements attitudes towards death, decreased existential distress, and increases in overall quality of life. The authors of the study reported no adverse effects, either medical or psychiatric.

Limited research has also indicated that symptoms associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) can also be reduced by using psilocybin. After hearing anecdotally about the association between symptom mitigation and psilocybin, Moreno et al performed a random, double-blind test on nine patients with OCD between 2001 and 2004. They tested four dosage levels (sub-hallucinogenic, low, medium, and high) at least one week apart. Of the nine patients, eight showed a greater than or equal to 25% decline in symptoms per the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale 24 hours after ingesting psilocybin. Six of the nine saw a decrease of 50% 24 hours after the session. These effects did not appear to have any correlation to dosage.

Individuals who are struggling to break their dependence on alcohol or nicotine may also benefit from psilocybin. In a study published in 2015, Borgenschutz et al conducted a proof-of-concept study by administering psilocybin to ten volunteers with alcohol dependency. While the psilocybin did not result in abstinence, all patients involved decreased the amount they used alcohol. A similar study currently being conducted by Dr. Kelley O’Donnell of New York University has also found that psilocybin may be able to potentially help patients with alcohol use disorder. “Some people have really profound psychological experiences that shift the way they think about themselves and the way alcohol is affecting their relationships,” O’Donnell told an audience during a presentation at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in San Francisco last month. “Therapy can work with that shift in meaning [to create] lasting change.”

Meanwhile, 15 cigarette smokers were enrolled in a 15-week open-label pilot study that included cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), as well as psilocybin administration at weeks 5, 7, and 13. Throughout the first four weeks, patients were allowed to smoke, though they were required to participate in CBT. They were then to quit smoking during the fifth week, which coincided with their first dose of psilocybin. Johnson et al, who published the study in 2017, reported that 80% of participants were still smoke-free at the six-month follow-up; 67% were smoke-free a year after quitting; and 60% were still not smoking when they performed their long-term follow-up (range = 16-57 months). The results are significantly better than those produced by CBT alone.

Individuals who are not struggling with the existential gravity of death, OCD, or addiction have also reportedly benefitted from using psilocybin. In articles published in 2006 and 2008, Griffiths et al found that patients’ moods and attitudes improved following the consumption of psilocybin, and that these effects were still discernible to the 36 patients involved in the study well after the initial experience. 67% of the 36 patients involved in the 2006 study even said that it was among the top five most meaningful experiences in their lives two months after the session. 14 months later (16 months after ingesting the psilocybin), these results were largely unchanged. 58% still ranked the psilocybin session as one of the top five most meaningful experiences in their lives; 64% said it increased their sense of well-being or life satisfaction to either a moderate or an above-moderate degree; and 61% believed the experience was associated with a positive behavioral change.

It is unclear how psilocybin produces therapeutic benefits that span months despite only being acutely effective for a few hours. It is possible that it may disrupt synaptic networks in the brain, thereby leading to the alteration of and re-establishing of these networks. It has also been proposed that psilocybin may have anti-inflammatory effects on the brain that specifically target serotonergic systems. If this is the mechanism of action, psilocybin could be a useful tool in combatting mental illnesses like depression, anxiety, and even posttraumatic stress disorder. However, we have only seen the tip of the iceberg. More research will be needed to establish the validity of either of these claims.

To conclude, it is important that clinicians and mental health professionals keep in mind possible alternatives that may exist beyond the scope of conventional treatments—of which psilocybin is but one example. However, as mentioned, we need to step forward with caution because the data is still quite limited. There is reason for hope and optimism about the potential utility of psilocybin, provided it is administered in an appropriate environment and with people present who can provide support. As beneficial as psilocybin may be, it is still a very powerful and currently illegal drug.

0 Comments on "Psilocybin 101: How “magic mushrooms” could help patients with anxiety, depression and addiction"