As seen on Psychology Today.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a progressive neurological disease that destroys the neurons that control voluntary muscle movements. The first symptoms of ALS are typically weakness in the limbs and muscle twitches, but the illness eventually disrupts patients’ abilities to move, speak, and even breathe. Treatments exist to extend patient quality of life, but only for a matter of months. There is currently no cure for ALS, and those who develop the disease typically die from respiratory failure within 2-5 years following the emergence of symptoms.

Researchers have yet to determine a full etiology for ALS. Genetics does play a partial role, with between 5% and 10% of those diagnosed with the disease being genetically predisposed to it. This is known as familial ALS (fALS). The remaining cases emerge following exposure to environmental hazards and are known as sporadic ALS (sALS). A strong association between cigarette smoking and sALS has been observed, while studies into other environmental factors have produced less conclusive results. A full understanding of the disease’s pathogenesis remains elusive.

ALS has long bene classified solely as a neurological motor neuron disease, but a growing body of evidence has shown that patients frequently develop comorbid psychiatric symptoms, as well. Nearly 15% of ALS patients fulfill diagnostic criteria for frontotemporal dementia (FTD); between 14% and 40% of patients show signs of behavioral disturbances; and impairment in verbal fluency and executive functioning has been observed in between 34% and 55% of patients. A genetic correlation between schizophrenia and ALS has also been established (McLaughlin et al (2017)). Data suggests that there may be a shared disruption in cortical circuity underlying both disorders and that these disruptions may arise due to a combination of several seemingly disparate factors, including an unhealthy gut.

Gut Feelings

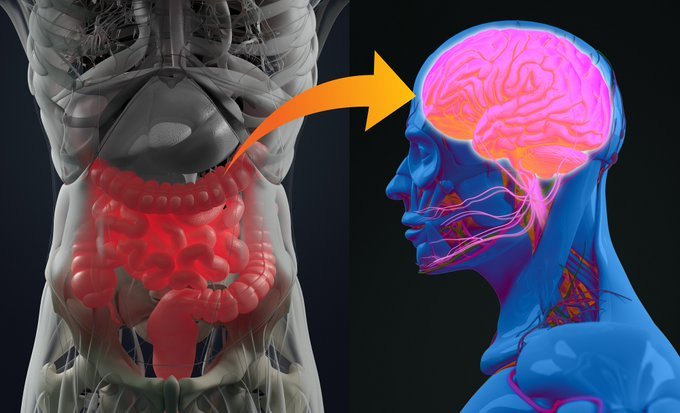

The gastrointestinal tract, or gut, runs from the mouth to the anus and includes all the organs that help us digest food. In addition to digestion, the gut is home to the enteric nervous system (ENS), which is a network of approximately 100 million nerve cells that communicate with one another using the same neurotransmitters found in the brain: norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, etc. The ENS does not merely communicate with itself; it also uses these neurotransmitters, as well as electrical signaling, to communicate bidirectionally with the CNS via the gut-brain axis.

The gut is also home to a diverse cast of microorganisms (bacteria, archaea, fungi, etc.) that have a mutually beneficial, symbiotic relationship with us, their hosts. And it is a big cast. While the exact ratio of human cells to microbial cells is a matter of some debate, it is clear that our guts serve as home to trillions of microorganisms, including upwards of 40,000 different species of bacteria alone. In exchange for providing them with room and board, our gut florae help keep us healthy by aiding in macronutrient metabolism and absorption, maintaining gut motility and the integrity of intestinal barriers, fighting against foreign pathogens in the GI tract, and helping to regulate the endocrine system, and most importantly our immune system.

When our gut microbiota’s health suffers, be it due to increased stress, poor diet, sleep disturbances, or antibiotic exposure, it falls out of balance and we enter into a state of dysbiosis. In the short term, this typically means a localized immune response, an increase in the production of proinflammatory cytokines, and inflammation. We may experience some discomfort or diarrhea, but the issue tends to fade away on its own.

When our gut experiences a protracted state of dysbiosis, the results can be far more severe. The integrity of the intestines may be compromised leading to the release of endotoxins, neurotoxins may be released via the gut-brain axis, or mistakes in the folding of proteins may occur that can lead to the creation of Lewy bodies (which are associated with dementia and Parkinson’s disease). In either case, the result is a proinflammatory state throughout the body that can compromise the immune system, leading to increased susceptibility to disease and making any disease that one does contract more severe. Many of those who are at an increased risk of developing severe symptoms of COVID-19 are also in a proinflammatory state due to severe obesity or conditions like type 2 diabetes mellitus and high blood pressure. Furthermore, proinflammatory states also can lead to neuroinflammation, which is associated with a host of psychiatric illnesses, from mood and anxiety disorders to schizophrenia.

In other words, when our gut biomes suffer, our minds suffer.

ALS and the Gut

New research is finding that neuroinflammation and gut dysbiosis are also associated with symptoms of disorders that fall outside of the realm of psychiatry, including ALS. A paper published by a group in Israel (Blacher et al (2019)) demonstrated in animal models that larger populations of some gut bacteria (including Ruminococcus torques and Parabacteroides distasonis) are associated with increased severity of ALS symptoms, while larger populations of other gut bacteria (particularly Akkermansia muciniphila) are associated with reduced severity of ALS symptoms. Meanwhile, researchers in Northeast China (Li et al (2019)) found that too large of a population of A. muciniphila (in conjunction with decreases in Lactobacillus) is positively associated with impairments to the immune system, thinning of intestinal mucus barriers, and Parkinson’s disease.

While all of this can make your eyes glaze over as it becomes evident how complex the human body is, what this emerging field of research (known by the daunting name of psychoneuroimmunology) reveals is that diseases like ALS are not just neurological disorders; they impact multiple systems throughout the body, systems that we for years thought barely communicated. That patients with ALS have comorbid psychiatric symptoms, concomitant immunological irregularities, and gut dysbiosis strongly suggests that any successful treatment must seek to address these multisystemic problems and restore balance to them. In other words, trying to treat the neurological symptoms associated with ALS or the psychiatric symptoms associated with schizophrenia may be futile if there is no attempt to rectify concurrent gut dysbiosis. It would be like fighting a fire on one front and feeding it oxygen on the other.

What the Gut Wants

As the studies mentioned above show, there is no one silver bullet when it comes to treating gut dysbiosis. Rather, avoiding stressors that lead to imbalances appear to be key. Some of these stressors include antibiotic exposure, sleep disturbances, lack of physical activity, psychological stress, and diets that are low in fiber and high in fats and processed sugars.

To help promote gut health and to reduce the risk of developing dysbiosis, we should try to exercise more, learn how to manage our stress better, and eat a diet that is nutrient-dense and high in fiber.

0 Comments on "A Gut Feeling About Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: The Mind Body Connection"