A recent paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association has revealed some disturbing statistics about the side effects of many of the drugs we take. To start, over one-third of Americans are currently taking at least one medication that lists depression as a potential side effect. The number of Americans currently taking at least three such medications is 9.5 percent. Even more shocking, the number of Americans who are taking medication that lists suicidal symptoms as a potential side effect is 23.5 percent.

“It was both surprising and worrisome to see how many medications have depression or suicidal symptoms as a side effect,” said Dima Mazen Qato, the lead author of the paper. Dr. Qato, an assistant professor and pharmacologist at the University of Illinois at Chicago, added that her paper leaves a lot of questions unanswered and, perhaps more importantly, that it reveals correlation—not a cause-and-effect relationship. “We didn’t prove that using these medications could cause someone who was otherwise healthy to develop depression or suicidal symptoms. But we see a worrisome dose-response pattern.”

This paper comes out in the wake of the recent study on suicide published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that set off alarm bells nationwide. It found that suicide rates jumped in every state except Nevada between 1999 and 2016. Half of U.S. states saw an increase of 30 percent or more.

Though the CDC study was heavy on statistics and raw data, it was hesitant to point fingers at specific causes for the spike in suicides around the U.S. With the release of the Qato paper, the public now has a potential villain: The pharmaceutical companies.

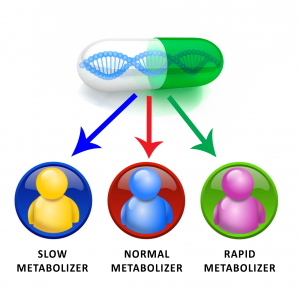

Before we grab for our pitchforks, however, there is one other key piece of information that has not been widely reported, largely because it concerns a technology that is still in its infancy. This technology is known as drug-gene testing (or pharmacogenomics or pharmacogenetics). It is the process of analyzing patients’ genetic codes to see how their bodies will metabolize and respond to certain medications. These tests can be used to better determine if a medication will provide one with effective treatment or if it will cause the patient to experience side effects that could be more detrimental to their well-being (iatrogenesis) than the disease it is supposed to treat.

Pharmacogenomics does not tell doctors what should or should not be prescribed; it is merely another tool to help doctors make the best decisions given the information available. Furthermore, there are numerous limitations to this technology. Steven L. Dubovsky, professor and chair of the Department of Psychiatry at the State University of New York at Buffalo, wrote in a recent paper published in Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics that “the hope that pharmacogenetic testing will result in unambiguous ‘personalized psychiatry’ should not lead to quick adoption of technologies that have not yet been demonstrated to reliably predict a specific course or a need for a specific medication, the choice of which remains largely empirical.” He also noted that “only a small number of reports have involved the prospective use of genotyping to make treatment decisions.”

He is right to be cautious of the technology because there are numerous variables that can impact a patient’s experience with a medication, and that pharmacogenomic tests do not always control for things like age, ethnicity, and the use of other substances such as tobacco, alcohol, hormones, or caffeine, among others.

It is currently an imperfect science.

Be that as it may, the technology is evolving. It is improving. David A. Mrazek, the late chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at the Mayo Clinic, acknowledged these limitations, but wrote that “progress in making predications of medication response has occurred,” in a 2010 paper published in Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. He also was optimistic that, in the future, “patients will no longer accept avoidable side effects and will demand basic testing prior to taking antidepressant or antipsychotic medications.”

This optimism is well placed. However, for it to become reality sooner rather than later there will need to be advances in the science, and these advances will require additional studies and research. This seems not only likely, but necessary. Pharmacogenomic testing should go hand in hand with the use and development of medications because it can improve the manner in which researchers measure the efficacy of said medications. In many ways, it enhances them because it allows doctors to better understand how a patient will respond to a medication and reduces the amount of trial and error necessary to ascertain the proper pharmacological regiment for each individual patient.

This is something that should be celebrated. Medication is necessary for the effective treatment of patients with mental health disorders, but there currently are risks. If we can reduce those risks by better understanding how medications interact with the brain chemistry of specific patients, we can reduce the risk of prescribing medications that will have a negative impact on patients. Though it has its limitations and is imperfect at present, drug-gene testing has the potential to do just that.

With time and effort, it could be honed to become an effective tool to both improve clinical psychopharmacology and combat the mental health crisis in America. That it is imperfect at present should not be a reason to ignore the potential benefits that it could have in the future.

1 Comment on "Pharmacogenomics: Drug – Gene Testing"